Marie Curie and the First Portable X-Ray: When Science Went to the Front Lines

Written By: Roger Boodoo MD

Marie Curie was the first woman to win a Nobel Prize in Physics for research on radioactivity, a term she coined. She later won a second Nobel Prize in Chemistry. Fewer people remember her wartime service and her choice to put science in the battlefield. During World War I, she attempted to donate her Nobel medals to support the war. When the bank refused to melt them, she bought war bonds instead. Most of all, she scaled portable radiology by engineering, training, and deploying mobile X‑ray units known as petites Curies. That work changed battlefield medicine and, in time, everyday healthcare.

Bringing Diagnostic Imaging to the Battalion Surgeon

In the autumn of 1914, German forces approached Paris. Curie placed her laboratory’s radium in a lead‑lined container and sent it to a bank vault in Bordeaux. She then returned to Paris to help. City hospitals had X‑ray machines. Battalion aid stations near the frontlines did not. Battalion surgeons were operating on casualties using pure instinct and clinical judgment, without any diagnostic imaging.

Curie’s answer was practical and bold. She outfitted 1910-era trucks as mobile radiology labs. Each truck carried a generator for power, an X‑ray tube, film, and a small darkroom. She recruited and trained teams to run the units. The first truck supported care around the Marne river. More followed as funding and vehicles arrived. By the end of the war, she had helped field about twenty mobile units, set up about two hundred fixed radiology rooms, and trained about one hundred fifty women. Her network performed well over a million examinations. Her effort brought capability to the point of care. Teams localized fractures, shrapnel, and bullets, which improved triage and surgical outcomes.

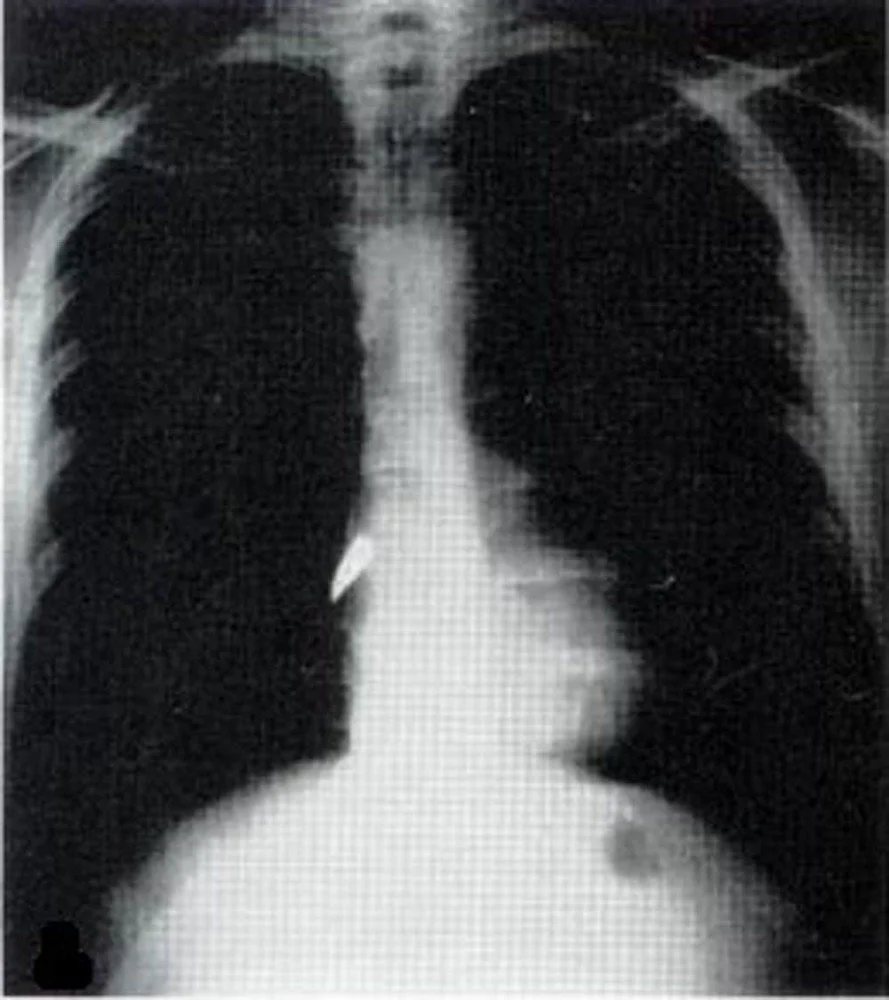

Chest radiograph reveals a bullet lodged closely to the right heart border.

How She Built Speed at Scale

The radiology trucks, petite Curies, needed electricity, so the engines drove generators. The teams needed skill, so Curie taught the physics of electricity and X‑rays, anatomy, positioning, and film processing. The units needed reliability, so she learned to drive, to change tires, to repair equipment, and to keep the workflow moving. When official support lagged, she raised funds, persuaded donors to contribute vehicles, and kept going. Banks recognized the symbolic value of her Nobel medals and refused to melt them, and she redirected that determination into financing and organizing the service. She treated the work as both patriotic duty and scientific investment because her field teams were directly improving the Army’s medical care.

Early radiology operators suffered burns from overexposure. Curie understood the risks and later wrote one of the first practical texts on radiology in wartime and on safety at the bedside. She built doctrine while she trained the first generation of radiology techs.

The Physics Behind the Vans

Wilhelm Röntgen’s discovery in 1895 gave medicine a way to see through the body. Curie and Pierre Curie went further. In 1898 they announced polonium and radium and helped make radioactivity a measurable property of matter. Curie later isolated metallic radium. She was recognized with the 1903 Nobel Prize in Physics and the 1911 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. Just as important, the Curies published rather than patented their core methods. Standards, measurement, and sharing became part of radiology’s culture long before modern data formats existed.

From Trench-side to Bed-side

Imaging met patients where they were. By the 2000s, portable chest radiography was routine in ICUs, emergency departments, operating rooms, and wards. Teams placed and confirmed lines and tubes at the bedside and caught complications when transport was risky. Ultrasound and CT traveled in many settings to include wartime medical care. Curie’s principle was visible in every exam.

Portable became ultra‑portable and intelligent. Battery‑powered digital systems rolled to the bed and reached remote clinics. Handheld ultrasound paired with smartphones expanded access. Public health programs used mobile X‑ray with computer‑aided detection for tuberculosis screening. Even MRI became mobile in select environments. Mobility combined with intelligence moved from novelty to practice.

People carried the advantage. Curie built operators as deliberately as she built equipment. Modern radiology continued to succeed on workflow, training, and tight feedback loops between the bedside and the reading room. Protocols, positioning discipline, and image‑quality review turned capability into consistent care.

Why It Still Matters: The Marie Curie Playbook

Imaging volumes have continued to rise while clinical teams are increasingly stretched thin. The lesson from Marie Curie’s wartime ingenuity still applies: put capability where decisions happen. Curie didn’t wait for wounded soldiers to reach city hospitals, she moved imaging to them. That mindset remains medicine’s most reliable force multiplier.

We must engineer for reliability in real conditions, not just in controlled environments. This is the essence of the Marie Curie Playbook: practical innovation, disciplined execution, and service under pressure.

The next frontier is artificial intelligence at the point of care - systems that bring intelligent insight to clinicians as seamlessly as Curie’s X-ray vans once brought imaging to the battlefield. The mission hasn’t changed; only the tools have.

What This Means for HOPPR

Curie brought imaging to the point of care. At HOPPR, we bring vision foundation models to the point of care.

API‑based inference inside the workflow. Insights appear in the viewer, the PACS, the RIS, the EMR, and on devices.

Near real‑time triage and routing. The right study reaches the right person at the right time.

Reliability built on a Medical-Grade AI Platform. Versioned models, monitoring, audit trails, and data provenance.

Enablement over replacement. Training and change management so clinicians trust and use the tool. Curie invested in her operators. We do the same.

Personal Perspective from the Field

I served as a battalion surgeon with the United States Marine Corps. On the worst days, sandstorms grounded air support and delayed medical evacuation. In those moments I felt most alone. The longest distance in medicine was the space between a patient and the capability they needed. Curie shortened that distance with petites Curies. At HOPPR, we aim to shorten it further with secure APIs and reliable AI so answers arrive where care happens.